“Archives — force” — said to me one day, Kirill M. Anderson, the former Director of the Russian state archive of socio-political history in Moscow. He talked about the first Director founded in 1919, the Institute of Marx and Engels: old Bolshevik David Ryazanov did not tolerate officials of the Communist party, which constantly require documents to confirm the ideological positions or denigrating the enemies.

One day he got a letter from Karl Marx, waved it in front of the nose of the astonished head of the party and shouted: “Here’s your marks. Now go away!” In 1931 Ryazanov argued with Stalin, and in 1937 he was arrested, and a year later shot.

Like thousands of other foreign publishers, scholars and journalists rushing to Moscow in January 1992, I came to the national archives after made by Boris Yeltsin in December 1991, the statement of intent to open secret Soviet archives. (I came on behalf of Yale University). Power, which was used by Mr. Anderson felt there almost live.

Many of these made in the archives of the discoveries turned some standard ideas about cold war spying in the Communist party of the USA, Stalin’s Great terror, the fate of writers and artists, and much more. Some new studies have confirmed previous point of view; for others, it shook deeply held convictions. But the greatest contribution can be traced, undoubtedly, to facilitate the process of deepening and making a living shade around the many components of a comprehensive phenomenon of Soviet communism and the character of Joseph Stalin.

I once asked a Russian historian, could we get to the essence of the archives of the KGB — the secret police of the Soviet Union — on a particular issue. “Of course — he replied slyly. — Only the entities of the KGB lot.”

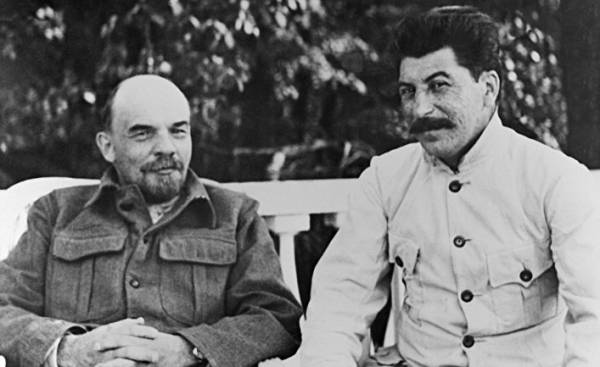

One of the most vague issues is related to the nature and causes of the Stalinist terror and the question as to whether Stalin broke with the political course of Lenin or continued it. Behind this lies the question of institutionalization of violence in Bolshevik culture and the Soviet state.

Although the unconditional recognition of the use of political violence appeared in the early Russian revolutionary movement, returning to the Manifesto of the “catechism of a revolutionary,” 1869 designed by Sergey Nechayev, the policy of Lenin and the Bolshevik party initially relied not on terror. However, the extraordinary circumstances of the civil war in the period from 1917 to 1922, claimed the lives of about seven million people, coupled with the ruthless economic policy of Lenin led to the poverty and despair of millions of people left without food, livelihood, shelter and sense of security.

Draconian methods of the Soviet Union in respect of the supply of grain caused a massive uprising of peasants. The nascent Bolshevik regime, it was necessary to prevent starvation in the cities, Lenin, not seeing another option, issued in August, 1918, a decree that was later discovered in a secret archive and read as follows: “Hang (hang necessarily, so that the people see) no fewer than one hundred notorious kulaks, rich men, bloodsuckers.”

“To publish their names, — he commanded. — To Rob them of all the bread. Designate hostages.”

“To do so, — he continued, — that for hundreds of versts around the people saw, awe, know, screaming, suffocate and strangle bloodsucking kulaks.”

And he added this chilling paper with the words: “Find tougher people”.

The following month, he ordered: “to prepare Secretly the terror: it is necessary and urgent.”

Lenin used terror against the sworn enemies of the state. Stalin turned him against the government and Soviet society. Stalin continued Lenin’s, but surpassed it.

The 7th of November, 1937, the anniversary of the October revolution, at a meeting of leaders of the Politburo, Stalin proposed a toast which was later published in his diary recorded the Bulgarian Communist and the head of the Comintern, Georgi Dimitrov.

“I want to say a few words, maybe not a holiday, — he declared. — The Russian tsars did much wrong. They plundered and enslaved the people. But they did one good thing — made a huge state, to Kamchatka. We inherited this state.”

He continued: “We joined the government so that each part, which would be isolated from the common socialist state, not only would be detrimental to the latter, but could not exist independently and would inevitably fell into another bondage. Therefore, anyone who tries to destroy this unity of the socialist state, seeking to separate from its individual parts, and nationality — he is an enemy, a sworn enemy of the USSR. And we will destroy every enemy, was he an old Bolshevik, we will destroy all his family, his family. Everyone who by their actions and thoughts — Yes, thoughts — encroaches on the unity of the socialist state will ruthlessly destroy. Defeat all enemies until the end, themselves, their family!”

What the members of the Politburo approvingly replied: “For the great Stalin!”

By the time the internal enemies of the Bolshevik government was almost completely destroyed, even the stubborn peasants, destroyed during the famine of 1932-33. 17th party Congress of 1934 was proclaimed the “Congress of victors”, and Andrey Zhdanov, head of the Leningrad party, and a favorite of Stalin, was able to declare at last in the same year the Congress of Soviet writers that “the main difficulties we are facing in socialist construction have already been overcome”.

The paradox is that Stalin unleashed the Great terror in 1936, in times of relative peace and stability. Hordes suddenly appeared in Soviet society, enemies were largely far-fetched. Millions of innocent people were arrested, tortured and shot, unproven and in accordance with the Kremlin quotas. Stalin was not bluffing: guilty could be literally anyone.

Bolshevik veteran and editor of the newspaper “Pravda” Nikolai Bukharin was one of these enemies: in February 1937 he was arrested, and in March 1938 was shot. His letter of 10 December 1937 he wrote to Stalin from prison cell — nothing more than incoherent and pathetic message from the doomed a man to death. But, surprisingly, he not only confirmed what Stalin told the Politburo a month earlier, but also admitted his role in the establishment of a mechanism in the turbine which sucked and himself.

“There are some big and bold political idea of the General cleaning, he wrote. This Shoe captures a) guilty, b) suspicious and C) potentially suspicious. Without me here could not do”.

An authoritarian state that drew in my head, Bukharin, was based on a constant state of destabilization in which the necessary element of state control are disruption and fear. The writer Lydia Chukovskaya in his unnerving novel “Sofia Petrovna” (1939), which in Russia was not published until the end of 1980-ies, has introduced fear as a key element of this inside-out world. The main character “was now afraid of everything and everyone,” Chukovskaya wrote. “Maybe it is already called in the police to take away the passport and send a link? She was afraid of every call”.

Undermining public order, rule of law, engendering fear in the very nature of individual consciousness and the spread of distrust were important towards the set goals Stalin eliminate any threats to his absolute power. In the years of the Great terror, Stalin not only eliminated his potential rivals, but also sent all over the country a clear message: once the suspicion could fall on Bukharin, Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev, confidence was not to anyone.

According to one report, Stalin kept a letter from Bukharin in the top drawer of his Desk, where he was found after his death but published only after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

With the end of the Second world war, the people won a great victory over Hitler, but Stalin recognized that along with the deterioration of physical health decline and went and the power of his personality. His response was the preparation of the second wave of terror.

We note again that the insured was not nobody. Stalin was enraged by the fact that his foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov was allowed to publish in the newspaper “Pravda” full text of the speech of Winston Churchill. Molotov did not recognize their enemies. Zhdanov, at that time one of the most powerful Politburo members also came to Stalin in disgrace when his son Yuri, the head of the scientific section of the Central Committee, held a closed workshop to discuss the work respetadong figure in Stalin’s government, agronomist-the charlatan Trofim Lysenko.

Stalin retaliated the old-fashioned way: physical torture as a method of dealing with political opponents; the dissemination of paranoia, fear and mistrust; inventing enemies; and, positioning himself as the only worthy leader in times of crisis. Through manipulation, favouritism, cruelty and cunning Stalin provoked the attack on the state itself. His power has spread outside of official structures, and the culmination of the final phase of Stalin’s tyranny was the “doctors ‘ plot” in 1953 — made-up crisis, in which prominent Jewish doctors were accused of plotting against the Soviet leadership. This new, which is a continuation expressed in the toast 1937 threat conspiracy have generated even greater potential distress due to the onset of the cold war era.

When Molotov did not find his name among those who allegedly intended to kill Jewish doctors, he realized that he was doomed. In this he was not alone: Anastas Mikoyan, Kliment Voroshilov and other former henchmen of Stalin was afraid that it was their time. When in 1952 the Chairman of the KGB Semyon Ignatiev was not fast enough to stamp a false recognition of the Jewish doctors Stalin threatened to “shorten it on the head.”

“Beat, beat, nearly to death beat” — he snapped at the chief of security. Soon after Ignatieff suffered a heart attack and was removed from office.

“Look at you,’ said Stalin in December of that year, gathering their close associates. — Here you have the blind kittens do not see the enemy; what will happen without me — die country, because you can’t recognize the enemy.”

Only he, Stalin, was able to lead the people, because only he, Stalin, could see the enemy. Only Stalin’s death in March 1953 saved from the destruction of a huge number of people, and maybe the rest of the world. Five months later the Soviet Union exploded the first hydrogen bomb.

Jonathan Brent, editor — in-chief of the series “Annals of communism,” published by Yale University press. In the period from 1992 to 2009 worked in the Soviet archives. Is the Executive Director of the Institute for Jewish research YIVO and lecturer at Bard College.