February 23, Russia celebrates Defender of the Fatherland Day, formerly Day of the Soviet Army and Navy. In recent decades, this holiday has lost its original meaning, and from professional holiday of the military has become an occasion to give gifts to men.

About how this day of February 23 was reinterpreted in the public consciousness and on the role that was played by the Army, oDR spoke with Mikhail Gabovich, a sociologist and researcher at the Einstein Forum in Potsdam and co-Director of the research project “the monument and the festival: an Ethnography of the Victory Day”.

– Michael, Your research team has carried out a huge project about the Ninth of May. You were able to show that around this holiday, there is a wide range of what You call “commemorative practices” — ceremonies, rituals, collective action, expressing the attitude of the past. And what happens on February 23? What is this holiday? What sense in it is now invested?

Mikhail Gabovich: that is commemorative of the practice in the day is not observed. No one remembers the mythical “Victory of red Army over Kaiser troops”, which to this day encourages the act. Except occasionally copy some practices commonly associated with the may 9 or June 22 — conduct of burial of the remains of soldiers or to commemorate “those who at all times was defending the homeland”.

The ninth of may refers to a specific historical date, despite the fact that in fact, this holiday has acquired the features of cyclical ritual, such as Passover. And on February 23 was a holiday theme, no specific events are not bound. It is interesting to observe its evolution. Technically from the Day of the Soviet Army and Navy, he turned into the Defender of the Fatherland Day, and, in fact, just in the “male” day. Even when I worked in the editorial of the liberal New Literary Review in Moscow, all men on February 23 gave vodka and Cologne. That is, any correlation not only with the specific WWI or the Civil war, but the history is completely lost.

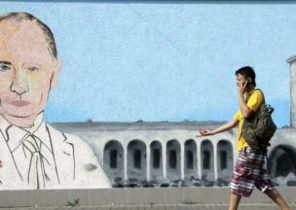

In this sense, I think, February 23 illustrates a generalization of militarism in the Russian society. Very much of what today has become a common social repertoire — including the celebration of the 23rd February and the 9th of may as the holidays — began as a internal military practice. Many of the practices in the 1960s and ‘ 70s formed the basis of the Brezhnev cult of Victory, before it was developed within the army. Directly after the war monuments were built by the army itself — largely for themselves. In the Russian Federation many of the first monuments of the glorified marshals or generals, and even the first monuments of concrete buildings is often put before the Houses of the Officers. All this mattered not only for the soldiers who returned from the war and joined the civilian life, but for the Soviet Army. The same can be said about February 23, and other dates and practices that were originally addressed to the acting forces, and then, because of the important symbolic role of the army, became General.

— There are more important point connected with the distribution of power. Liberal critics, watching Russia, it is often said that in Russia such institutions as the army, and now the Orthodox Church has enormous power. In fact, their real political power is strictly limited. I don’t know of a single case, for example, that the Church made the resignation at least of the Governor. But the Church has a very great symbolic power: without her now not to imagine any holiday, any cemetery, any new memorial.

The same applies to the army. In Russian history there is no example of a successful military coup, unlike, say, Turkey or Egypt. There’s virtually not a single example, when commanders have been able in the political sphere to act independently and successfully, and not as allies of some political leaders. For example, in 1953-56. Khrushchev is talking to the recently disgraced Zhukov and uses his reputation to their advantage, for inner-party struggle — and then again pushes it. No hint that the army can play any independent political role.

But she is gaining symbolic power. National holidays are those associated with military success. We see this today and the example of the new National cemetery. It was created at the initiative of the Ministry of Defence, in its custody and officially called the Federal Military Memorial Cemetery. This is the cemetery where are buried the President and other higher ranks — and while many people are not even aware of its existence. The initiative for its creation came from the army, she also supervised its construction, and determined its symbolism. The wide public resonance, this place got. Thus, on a symbolic level, the army is of great importance — but only as compensation for total subordination to the political leadership.

– What role the army plays in commemorative practices that You study in processions, rituals, demonstrations?

— Visually, the army is not present very much. In Russia, for example, in many places, where we conducted the study, is a very important practice is the collective view of the Moscow parade or local marches, timed in time for the start. Here the main role is played by the military, military equipment, and so on.

But we see that in the organization of the festivities, asking thematic vector, the army plays rather a subordinate role, and this role is becoming less and less from year to year. The army drove the veterans and today’s veterans of the Afghan and Chechen wars. Often they are the main organizers of the festivities, the installation of monuments and so on. Then, the increasing role played by re-enactors and various military paraphernalia, military uniforms, caps worn by the children, and of course ribbon. To the person associated with the army, often have to overcome considerable internal resistance at the sight of the ribbons, because he knows that the guard tape is a very specific distinction, the reward for specific achievements. And since 2005, the initiative does not even army, and Moscow journalist George ribbon became a common symbol of all, which are all up to cats, dogs and strippers. It is clear that if on the feasibility of such a symbol was originally asked to be generals, they would have simply banned. But the generals here to vote had not.

To take another example — the Immortal Regiment. Although it was created by liberal, critical Tomsk journalists, there is still militarism all the time: that the terminology used on their website, and the form of the March-parade. It is clear that all of this is taken from the experience of a certain generation of Russian men who passed through military service — but the paraphernalia and rituals rituals to the present army do not have a relationship. To summarize: while the symbolic militarism is spreading throughout society, the value of the army to these practices falls.

– And the army itself is able to create some new practices? It has now its own founding myth? I mean a modern army.

— A myth is, of course. But it seems to me, to a greater extent than during the Second world war, is created in dialogue with non-military ideology. For example, if you take the Izborsky club or other national-Patriotic associations of recent years, we will see that in the army there are generals, favorably relevant to their ideology. You may recall another support Dugin Academy of the General Staff in the 1990s. While the army itself is almost not able to generate something new yourself.

– While we’re talking about the army, continuously participating in hostilities. Why not build a meaningful public narrative?

Narrative is built, of course, but not by the participants themselves. Not the army command, which in ideological terms behaves more passively.

Some practices that proceed from the combatants, reach society shifted in time. Today a very large role played by veterans of the Afghan war — but they are very long to achieve it.

We all remember that in 1980-e and 1990-e years, in fact they were denied public recognition, and they developed their practices, myths almost in isolation from society. And there is a parallel with what happened after 1945. Some influence on society as a whole practices developed by front-line soldiers, began to have only when these veterans have taken leadership and public interest positions.

Same with the Afghans. Today they are 45-50 or more, they are leaders in government, business — and it allows them to implement their ideas. They have the resources.

And those soldiers who are fighting in Syria today and come back — they are such a role does not play. They are, at best, become passive objects commemorative of the policy, and at worst, if we are talking about the Donbass, their fate simply glossed over, as was the case with the funerals of the paratroopers in Pskov.

– The Defender of the Fatherland Day is fundamentally different from other popular professional holidays, such as Teacher’s Day?

— February 23 ceased to be a celebration of the professional group — the military — and became a male-only holiday. It is likely that the profession of “military” had the sight of huge masses of people. Teachers, after all, almost every one of us one way or another is dealing with. And after the army in today’s Russia, contrary to the existing view, were not nearly all, even men. There is a huge class differences: if you were given a release, a reprieve for higher education or you’re bought off, you it is nothing to do with.

There are whole layers of society, not related to the army and just don’t know what it is. And besides, even if people have been through military service — they’re more in the army are not. That is, if a person once got out of the army, and now works in the office, its professional holiday is a holiday for office employees. In the fighting involved professionalized minority, belonging to certain social groups. Therefore, on the 23 February will be very different in Moscow or St. Petersburg and, for example, in Pskov, artëm and other cities and regions where the army plays a very important role as an employer.

There are class stratification and regional specialization. The Russian case, thus, it is not unique. For example, in America, in the 1970s protests against the Vietnam war reached such a scale because almost everyone, including intellectuals, knew someone who served in the army and or passed through Vietnam, or could there at any time be. And the war in Iraq — after the first big wave of protest attitude was different, because the educated strata of society have had very little to do with the current troops.

– You learn how people in Russia remember the events of the Second world war, celebrated on 22 June and the ninth of may — Victory Day over fascism in Germany. How difficult — or, conversely, it is easy to do with this topic?

— On the one hand, to tackle this issue in Germany — it’s very satisfying, as here, probably even more so than in any other country there is a whole industry of memory research and the public discourse about memory. Moreover, there is a whole institutional infrastructure that supports such research. I, for one, am very grateful to the Foundation “remembrance, responsibility and future”, which has funded our commemorative collection on the Ninth of may, and, most importantly, our last meeting of the research network in Potsdam in November 2016. In addition, we are very supportive of the German-Russian Museum in Karlshorst, Berlin. The network of institutional support in Germany is very dense and goes far beyond academic science.

On the other hand, precisely because of the development of the discourse about memory, I’m in Germany are faced with very specific challenges. Here in the first place, it is customary still to talk about the memory, that is: on the representation of the past. And when you examine the memory, and commemoration, that is, what people do, not what they think, then often you face with lack of understanding. Here in recent years have a lot to say about cultures of remembrance —Erinnerungskulturen, use this concept as an overarching framework for these studies. And for what I do, it’s not always good, because in the view, not the action. This approach of historians, who compare the facts of the past with the idea of it.

And I’m not interested in what does it differ and how the memories of people from the views of historians, and the fact that we can observe today in the form of practices. For me, the question is: what do people do when they Express their attitude to the past? I have no problem to learn the “right” or “wrong”, people Express this attitude. To explain this approach in Germany is quite difficult. My colleague Manfred Hettling aptly wrote that in Germany there are monuments, but there is no commemorative. Therefore, when we examine what these monuments happens after I installed them — what ceremony, what are the rituals around them arise, what emotions they evoke in people, what happens to them may 9, February 23, or 3 Dec, here do not always understand what we do. Furthermore, since in Germany the study of memory is very much associated with the Nazi past, they present a very strong normative component.

So, in commemoration, we always have to indicate their own attitude. This leads to a certain politicization. Any practice that from the point of view of German culture of memory are considered ethically unacceptable — for example, the presence of the extreme right in Treptower Park, the Ninth of may — like disqualifiziert the object of study. And although as a citizen I have the regulatory framework is well accepted, the discussions on the study they can make it difficult. Let’s say someone came on Victory Day in uniform. The German colleagues immediately cause rejection is the militarism and therefore it’s bad. But my goal is not to condemn, but to understand why people this form wearing, what his motivation that he puts.