On Monday last week 11 people died and more than 40 were wounded due to the terrorist attack in St. Petersburg metro. This attack is just one of many that occurred during the entire violent history of Russia.

For many Western countries terrorism is a characteristic feature of modern society; this phenomenon is usually associated with political globalization. Of course, we in Sweden have something to talk about when it comes to murders and conspiracies, but they usually were associated with dissatisfaction of individuals, as in the case of the murder of Gustav III in 1792. Thank God, events like the one that occurred on 7 April on Drottninggatan, in all its horror, are perceived as exceptional. In Russia, this is different. There is a whole culture of terrorism, which sends a strong historical signals.

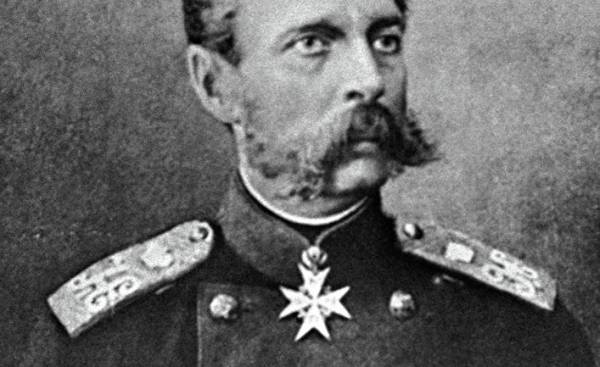

Terrorism has become a common weapon of the political opposition during the reign of Alexander II. The king sat on the throne in 1855, and went down in history as a relatively successful ruler. He expanded the borders of countries in Asia, suppressed the uprising in Poland, successfully waged war against the Ottoman Empire and abolished slavery Russian serfdom. However, this era marked by the increasing number of terrorist attacks. The terrorists were foreigners, and Russian. Many Polish patriots nothing so much didn’t like to be taken off the national “enemy number one”. Russian extreme left groups wanted the same thing: for them the king was a symbol of everything wrong with the Russian political system with its steel conservative autocracy and the many social failings.

So Alexander II, other members of the Royal family, led a dangerous life. Very dangerous. It lasted from one assassination attempt in 1866 to the other in 1867. In April 1879 he managed to avoid death, when at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg he was shot from a revolver Alexander Soloviev. In December of the same year was made an unsuccessful attempt to undermine the terrorists of the Royal train. In February 1880, the terrorists detonated the dynamite in his dining room: 11 people died, but the king survived. And so on. Alexander II was a living target, in the end he was left with no chance, especially after the Executive Committee of the terrorist movement Narodnaya Volya sentenced him to death in his proclamation. March 13, 1881 (March 1 of the then Russian calendar) in St. Petersburg, a bomb exploded under his carriage. The king survived, but when he came to himself on the street and ran up to the other terrorist and threw another bomb directly at him and this time he is killed (in case, if the second terrorist was missed, nearby stood ready and the third).

The terrorist tactics of the “people’s will” had two objectives: first, to get rid of the king and other hateful people, and secondly, to inspire the Russian masses for a General armed uprising. From the first they did really good, except for the fact that Alexander II was replaced by another king, archconservative Alexander III. In the end, to overthrow the monarchy, it took the First world war. Terror has meant that the already strained relationship between the king and the opposition became worse, the suspicion of the authorities has led to many references to Siberia, many were forced to flee abroad, and it seemed that the spiral of violence will never cease to spin.

Who wants to, of course, can still expand this overview of the history of public violence in Russia. And Ivan the terrible, and Peter the Great murdered their own sons. Catherine the Great was behind the murder of her husband. Paul I was murdered in his own bedroom. Purges of Joseph Stalin legendary: politicians and military officers tortured, forced to admit guilt to crimes they did not commit, after which they were eliminated. Replaced the armed attacks undertaken by Finns, poles and others in tsarist times, in modern history came much more violent and desperate Chechen terrorism. In short, public violence, both from their own authorities, and by the angry citizens for centuries been the part of Russian political culture.