Translation carried out by the project Newочем.

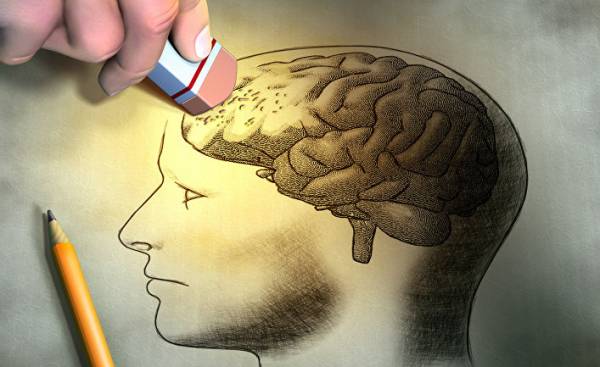

No matter how they tried, neuroscientists and cognitive psychologists will never find in the brain a copy of Beethoven’s fifth Symphony or copy words, images, grammatical rules, or any other external stimuli. The human brain was empty, of course not literally. But it does not contain most things that the people need — there’s even such simple objects like “memories”.

Our false idea of the brain has deep historical roots, but the invention of the computer in the forties of the last century especially has confused us. For more than half a century, psychologists, linguists, neuroscientists and other researchers of human behavior claim: the human brain works like a computer.

To understand the superficiality of this idea, let’s imagine that the brain is a baby. Due to the evolution of newborn humans, like any other newborn mammals, come into this world ready for effective interaction with him. Child’s vision is blurry, but he pays special attention to persons and quick to recognize the mother’s face among others. He prefers the sound of voices other sounds, he could distinguish one base speech sound from another. We are without a doubt built with an eye on social interaction.

A healthy newborn has more than a dozen of reflexes — ready reactions to certain stimuli; they are necessary for survival. The child turns his head in the direction of what tickles his cheek, and sucks anything that gets in your mouth. He holds his breath when immersed in water. He grabs things that fall in his hands for so long that it almost hangs on them. Perhaps most important is that the babies appear in this world with a very powerful learning mechanisms that allow them to rapidly change so that they could interact with the world with increasing efficiency, even if this world and not like the one faced by their distant ancestors.

Senses, reflexes, and mechanisms of learning — all things with which we begin, and in truth, these things pretty much if you think about it. If we didn’t have one of those possibilities from birth, it would be much harder to survive.

But there is something we are not born: information, data, rules, software, knowledge, vocabulary, ideas, algorithms, programs, models, memories, images, processing, subroutines, encoders and decoders, symbols and buffers and design elements that allow digital computers to behave in a manner that is somewhat reminiscent of the reasonable. Not only are we not born with it — we are not developing. Never.

We do not store words or rules that tells us how to use them. We do not create a visual projection of the stimuli, store to buffer short-term memory, and then not pass them in the store long-term memory. We do not extract information or images from registers of memory. This involved computers, but not the organisms.

Computers in the literal sense of the word process the information — numbers, letters, words, formulas, images. Initially, information needs to be encoded to a format which can be used by computers, and therefore it should be represented in the form of ones and zeros (“bits”), which are assembled in small blocks (“bytes”). On my computer, where each byte contains 8 bits, some of them represent the letter “K”, others — “On”, third — “T”. So all these bytes form a word “CAT”. One single image — say, a picture of my cat Henry on the desktop — represented by special drawing million of bytes (“one megabyte”), certain special characters that tell the computer what it’s a photograph, not a word.

Computers literally move these figures from place to place in different compartments of the physical storage allocated within the electronic components. Sometimes they copy the drawings, and sometimes alter them in various ways — for example, when we correct a mistake in the document or recusaram photo. Rules followed by the computer to move, copy, or operating these data layers are also stored inside the computer. Collected together the sets of rules referred to as “programs” or “algorithms.” The group of algorithms that work together to help us in some way (for example, when buying stocks or search online) called “application”.

Excuse me for this introduction to the world of computers, but I need to make it all very clear: computers are in fact working on that side of the world, which consists of characters. They do store and retrieve. They really treated. They do have physical memories. They really are controlled by algorithms in all that you do, without any exceptions.

On the other hand, people do not do that — never did and will not do. Given this, I want to ask: why do so many scientists talk about our mental health like we are the computers?

In his book “In our own image” (In Our Own Image, 2015) is an expert in the field of artificial intelligence Saridakis George (George Zarkadakis) describes six different metaphors that people have used for the last two millennia trying to define human intelligence.

In the first Bible, people were created from clay and dirt, which is then an intelligent God has endowed his soul, “explaining” our intelligence — at least grammatically.

The invention of hydraulic engineering in the 3rd century BC led to the popularization of hydraulic models of human intelligence, the idea that the different fluids of our body — the so-called “bodily fluids” — are related to both physical and mental functioning. The metaphor persisted for more than 16 centuries and all this time was used in medical practice.

By the 16th century was developed by automatic mechanisms, driven by springs and gears; they finally inspired leading thinkers of the time such as rené Descartes, on the hypothesis that people are complex machines. In the 17th century British philosopher Thomas Hobbes suggested that thinking arose because of mechanical vibrations in the brain. By the early 18th-century discoveries in electricity and chemistry has led to new theories of human intelligence — and again, they had a metaphorical character. In the middle of the same century, the German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, inspired by the achievements in the field of communications, compared the brain with the Telegraph.

Each metaphor reflects the most advanced ideas of the age that gave it birth. As was to be expected, almost at the dawn of computer technology, in the 40-ies of the last century, the brain’s principle of operation was compared with the computer, with the role of the warehouse were given to the most the brain, and the role of software is our thoughts. The landmark event, which began with what is now called “cognitive science”, was the publication of a book by psychologist George Miller’s “Language and communication” (1951). Miller suggested that the mental world can be studied using the concepts of information, computation and linguistic theories.

This way of thinking received its final expression in the small book “Computer and brain” (1958), in which the mathematician John von Neumann stated categorically: the function of the human nervous system is “primarily digital”. Although he acknowledged that then was, in fact, very little is known about the role the brain plays in thinking and memory, he drew Parallels with the Parallels between the components of the computer at that time and the components of the human brain.

Movable subsequent advances in computer technology and brain research, as well as an ambitious interdisciplinary attempt to ascertain the nature of the gradually evolving human intellect, in the minds of people firmly stuck on the idea that people, like computers, are information processors. Today this area includes thousands of research consumes billions of dollars of funding, it has created a vast body of literature, consisting of both technical and other articles and books. The book of ray Kurzweil “How to create a mind” (2013) illustrates this point of view, capitalizing on the “algorithms” of the brain, how the brain “processes the data”, and even at external similarity with the integrated circuits and their structures.

The metaphor of the human brain, built on information processing (hereafter, IP-metaphor, Information Processing — approx. Newoчем), in our day dominates the minds of the people, as among the inhabitants, and among scientists. In fact, there is no discourse about rational human behaviour, which would have taken place without the use of this metaphor, as well as the fact that such discourses could not occur in a specific era and within a particular culture without reference to spirits and deities. The justice of the metaphor of information processing in today’s world usually confirmed without any problems.

However, the IP metaphor is only one of many, this is just a story we tell to make sense of something we do not understand. And, like all the previous metaphor, this, of course, at some point will be discarded — replaced or another metaphor, or true knowledge.

A little over a year ago when visiting one of the most prestigious research institutes, I challenged scientists to explain rational human behavior without reference to any of the aspects of IP metaphors of information processing. They could not do, and when I again politely raised the question about this in subsequent emails, months later they never were able to offer. They understood what the problem is, not disown task. But they could not offer an alternative. In other words, IP the metaphor “stuck” to us. It burdens our thinking with words and ideas, so serious that we have problems when you try to understand them.

About logic IP metaphor is quite simple in the formulation. It is based on a false argument with two reasonable assumptions and about the only conclusion. A reasonable assumption No. 1: all computers are able to behave intelligently. A reasonable assumption No. 2: all computers are information processors. False conclusion: all objects that are capable of rational activity, are information processors.

If we reject the formal terminology, the idea that people are information processors just because computers are, sounds silly, but when one IP metaphor eventually become obsolete when it finally refuses, she will almost certainly be regarded by historians as we now look at the statements on hydraulic or mechanical nature of man.

If this metaphor is so stupid, why is she still ruled by our minds? What keeps us from being able to cast it aside as unnecessary, just as we reject the branch that blocks our way? Is there a way to understand human intelligence, not based on imaginary crutches? And what price will cost us such a long use of this support? This metaphor, in the end, have inspired writers and thinkers on a huge amount of research in various fields of science for decades. At what cost?

In the audience at the session, which I conducted over the years, many times I begin with the selection of a volunteer who is told to draw a one dollar bill on the Board. “More details,” I say. When it finishes, I close the drawing with a sheet of paper, pulls out a bill from his wallet, stick it on the Board and ask the student to repeat the assignment. When he or she finishes, I take a sheet of paper from the first picture and then the comments on class differences.

Perhaps you never saw such a demonstration, or, perhaps, you may have problems to represent the result, so I asked Jeannie Hyun, one of the interns at the Institute where I study, to do two drawings. Here is a picture “in memory” (note the metaphor).

But the picture that she made using banknotes.

Ginny was just as surprised by the outcome of the case may have surprised you, but that’s not unusual. As you can see, the pattern formed without the support of the bill, is terrible in comparison with what was copied from the sample, despite the fact that Ginny saw a dollar bill thousands of times.

So what’s the deal? Don’t we have “downloaded” in the brain “memory register” a “view” of what it looks like a dollar bill? Can’t we simply “remove” it from there and use to create the drawing?

Of course not, and even thousands of years of research in the field of neuroscience does not help to detect the performance of the dollar bills stored in the human brain, simply because it is not there.

A significant amount of research on the brain shows that in reality the numerous and sometimes extensive areas of the brain often involved in seemingly the most trivial task of memorization. When a person experiences strong emotions, the brain can activate millions of neurons. In 2016, the neuroscientist from the University of Toronto Brian Levin and his colleagues conducted a study, which was attended by people who survived a plane crash, which allowed to conclude that the events of the accident contributed to the increase in neural activity in the “amygdala, medial temporal lobe, the anterior and posterior midline and in the visual cortex of passengers.”

A number of scholars put forward the idea that specific memories are somehow stored in individual neurons, is absurd; if anything, this assumption only raises the question of memory to an even more complex level: how and where, ultimately, memory is stored in the cell?

So what happens when Ginny draws a dollar bill without using a model? If Ginny had never before seen the bill, her first picture will probably in no way be similar to the second. The fact that she saw a dollar bill before, has somehow changed her. In fact, her brain was modified so that it was able to visualize the bill — that, in essence, is equivalent to — at least partly — to re-experience the feeling of eye contact with bill.

The difference between the two outline reminds us that the visualization of something (what is the process of recreating the visual contact with what is in front of us) is much less accurate than if we really saw something. That is why we are much better able to learn than to remember. When we re-producyruet something in memory (From the Latin re — “again” and produce ‘new’), we must try again to survive the collision with the object or phenomenon; however, when we learn something, we just have to be aware that we have had the experience of subjective perception of that object or phenomenon.

Perhaps you have something to object to this evidence. Ginny saw a dollar bill before, but she never made a conscious effort to “remember” the details. You can say that, if she did, she might be able to draw the second image without using a sample dollar bill. However, even in this case, no image of the banknote was not in any way “stored” in the brain Ginny. She just increased her level of readiness to draw her compliance with the details, as well as, through practice, the pianist becomes skilled in the execution of piano concertos, without downloading a copy of the notes.

Based on this simple experiment, we can begin to build a Foundation free from the metaphors of the theory of intelligent human behavior — one of those theories, according to which the brain is not completely empty, but at least free from the burden of IP metaphors.

To the extent that, as we move through life, we are exposed to many originating from the us events. It should be particularly noted three types of experiences: 1) we observe what is happening around us (how to behave in other people, the sound of music, addressed to us the instructions the words on the pages, the images on the screens); 2) we are exposed to a variety of stimuli (eg, sirens) and an important stimulus (the appearance of police cars); 3) we are punished or rewarded for acting a certain way.

We become more effective if changed according to this experience — if we can tell a poem or sing a song, if we are able to follow the instructions given to us, if we respond to minor stimuli as well as on important if we try not to punish us, and often behave in ways to obtain rewards.

Despite the misleading headlines, no one has the slightest idea about what changes occur in the brain after we learned to sing a song or learn a poem. However, neither the songs nor poems were not “downloaded” into our brains. He just uporyadochennost so that now we can sing a song or tell a poem, if certain conditions are met. When we are asked to act, nor song, nor poem not “extracted” from some place in the brain — exactly the same as not “extracted” movement of my fingers when I drum on the table. We just sing or talk — and no extraction we don’t need.

A few years ago I asked Eric Candela — neurology of Columbia University, who received the Nobel prize for what he identified some of the chemical changes occurring in the neutron output synapses Aplysia (sea snail) after she learns something — how much time, in his opinion, will it take before we understand the mechanism of functioning of human memory. He quickly replied, “a Hundred years”. I didn’t think to ask him whether he thinks that the IP metaphor slows down the progress of neurology, however, some neuroscientists and really begin to think about the unthinkable, namely that the metaphor is not so necessary.

A number of cognitivists — in particular, Anthony Chemero from the University of Cincinnati, the author published in 2009 the book “the embodiment of cognitive science” (Radical Embodied Cognitive Science) is now absolutely deny the idea that the activity of the human brain is similar to the operation of your computer. The widespread belief is that we, like computers, conceptualize the world, carrying out calculations on his mental images, but Camera and other scientists describe another way of understanding the thinking process — they define it as a direct interaction between organisms and their world.

My favorite example to illustrate the huge difference between the IP approach and what some have called “anti-representational” view of the functioning of human body involves two different explanations of how the baseball player can catch a fly ball, given by Michael Makuta, now working at the University of Arizona, and his colleagues, in an article published in 1995 in “Science”. According to the IP approach, the player needs to formulate a rough estimate of various initial conditions of the ball — the force of impact, the angle of trajectory and all that jazz — and then to create and analyze an internal model of the trajectory, which, most likely, must follow the ball, after which it needs to use this model to continuously send and the time to adjust the movement to intercept the ball.

Everything would be fine and good if we were operating in the same way as computers, but Macbeth and his colleagues gave a more simple explanation: to catch the ball, the player should only continue to move so as to constantly maintain a visual connection with respect to the main base and the surrounding area (technically, adhere to the “linear optical trajectory”). It may seem complicated, but actually it is very simple and does not involve any computation representations and algorithms.

Two ambitious psychology Professor from the British City of Leeds University — Andrew Wilson and Sabrina Golonka — consider an example about a baseball player to some other that can be perceived outside IP approach. For many years, they wrote in their blogs about what they called “a more coherent, naturalised approach to the scientific study of human behavior… contrary to the dominant cognitivist neurological approach.” However, this approach is far from being able to form the basis of separate movements; the majority of cognitivists still refuse criticism and adhere to the IP metaphor, and some of the most influential thinkers in the world have made grandiose predictions about the future of humanity, which depend on the validity of the metaphor.

One of the predictions made, among others, the futurist Kurzweil, physicist Stephen Hawking and neurologist Randall Cohen says that since the human mind is supposed acts as the computer program would soon be possible to upload the human mind into the machine, so that we shall have infinitely powerful intellect and quite possibly gain immortality. This theory formed the basis of the dystopian film “Superiority”, in which the main role was played by johnny Depp, who played similar to Kurzweil a scientist whose mind was uploaded to the Internet — which led to disastrous consequences for mankind.

Fortunately, since IP is a metaphor in no way is not true, we will never have to worry about what the human mind will go mad in cyberspace, and we’ll never be able to achieve immortality by downloading it anywhere. The reason is not only the absence of conscious software in the brain; the problem is deeper — let’s call it the problem of the uniqueness — that sounds both inspiring and depressing.

Since no “memory banks” or “presentation” of stimuli in the brain do not exist, and since all that is required of us to function in the world, it changes the brain as a result of the acquired us experience, there is no reason to believe that the same experience changes each of us in equal measure. If you visit the same concert, the changes occurring in my brain at the sound of the Symphony No. 5 of Beethoven will almost certainly differ from those that occur in your brain. These changes, whatever they may be, are based on the unique neural structure that already exists, and each of which has evolved over your life filled with unique experiences.

As shown in his book “Remembering” (1932), sir Frederic Bartlett, this is why no two people will ever repeat the story they heard the same, and over time their stories will be more and more different from each other. Not created any “copies” of history; rather, each individual, after hearing the story, to some extent, is changing — enough so that, when later he was asked about this story (in some cases, after days, months or even years after Bartlett first read them the story) — they will be able to some extent to relive those moments when they listened to the story, though not very precisely (see the first image of a dollar bill above.).

I guess it’s inspiring because it means that each of us truly unique is not only their genetic code, but even that changes over time with his brain. It’s also depressing, because it makes the daunting task of neuroscience is almost beyond the imagination. For each of the everyday experiences orderly change may include thousands, millions of neurons or even whole brain because the process of change is different for each individual brain.

What’s worse, even if we had the ability to take a snapshot of all 86 billion neurons in the brain and then simulate the state of these neurons with the help of a computer, this lengthy pattern wouldn’t work on anything beyond the brain, in which it was originally created. Perhaps this is the terrible effect that the IP metaphor has made on our understanding of the functioning of the human body. At the time, as computers and in fact remain accurate copy of the information copy, which can remain unchanged for a long time, even if the computer itself was disconnected, the brain supports intelligence only while we are alive. We have no buttons “on/off”. Either the brain continues its activity, or we disappear. Moreover, as noted by the neuroscientist Steven rose in his published in 2005 the book “the Future of the brain”, a snapshot of the current state of the brain can also be meaningless if we don’t know the full story of the life of the owner of the brain — perhaps even detalisation environment in which he or she grew up (La).

Think about how difficult this problem. To understand at least the basics of how the brain supports human intelligence, we may need to clarify not only the current status of all 86 billion neurons and 100 trillion their intersections, not only distinguished the force with which they are connected, but also how every minute the brain activity supports the integrity of the system. Add to this the uniqueness of each brain, created in part due to the unique life path of each person, and the prediction of the Kendal starts to seem too optimistic. (In a recently published editorial column of The New York Times, the neurologist Kenneth Miller suggested that the task at least figure out the basic neural connection is “century”.)

Meanwhile, huge sums of money allocated to the study of brain activity, based on the often incorrect ideas and false promises. The most egregious case, when neurological research went awry, was documented in the recently released report Scientific American. It was about the amount of 1.3 billion dollars earmarked for running the European Union in 2013 the project “the Human brain”. Convinced charismatic Henry Markram that he will be able to simulate a human brain on a supercomputer by 2023, and that such a model will achieve a breakthrough in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders, the authorities of the EU financed the project without imposing literally no restrictions. After less than two years the project has evolved into the “twisted brain”, and Markram asked to leave the post.

We are living organisms, not computers. Deal with it. Let’s continue trying to understand themselves, but get rid of unnecessary intellectual goods. IP metaphor has existed for half a century, bringing a tiny number of discoveries. It’s time to press the DELETE button.