The translation is done Newочем.

In the fall of 1989 to the first year of Princeton University entered a young man named Alexi Santana (Alexi Santana), whose biography is extremely intrigued by the selection Committee.

Not having received almost no formal education, he spent his youth in the vastness of Utah, where he herded cattle, raised sheep and read philosophical treatises. Jogging in the Mojave desert prepared him to become a marathon runner.

Campus Santana quickly became something of a local celebrity. He excelled in school, receiving “excellent” in almost every discipline. His stealth and charm of the past created around him an aura of mystery. When the roommate asked Santana why his bed always looks perfectly made, he replied that sleeping on the floor. It seemed logical: he who all his life slept under the open sky, does not Harbor a special liking to the bed.

But that’s only the truth in the history of Santana was not a drop. After about 18 months, after enrollment, one woman accidentally recognized him as Jay Huntsman, six years earlier studied in high school, Palo Alto. But even that name wasn’t real. At Princeton in the end found out that actually it was James Hoag, 31-year-old man, some time ago, serving a sentence in Utah state prison for possession of stolen tools and parts off the bike. He left Princeton in cuffs already.

Years later houga was arrested several times for embezzlement. In November, when he was arrested for theft in aspen, Colorado, he again tried to impersonate another.

The history of mankind knows many equally skilled and experienced liars, what was Hoag.

Among them were criminals who spread false information, oplease them all around like web to get undeserved benefits. So did, for example, financier Bernie Madoff (Bernie Madoff), for many years received from investors billions of dollars until his Ponzi scheme collapsed.

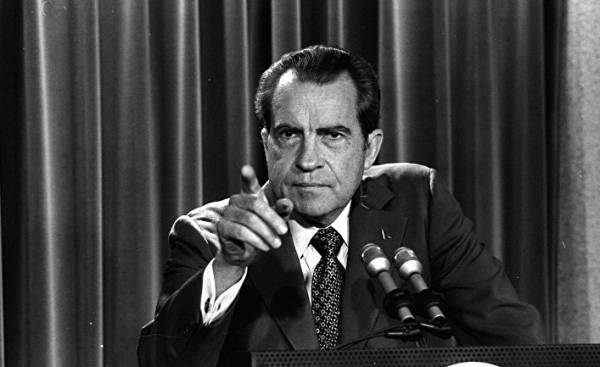

Among them were politicians who resort to lies to come to power or hold it. Famous example — Richard Nixon (Richard Nixon), who denied the slightest connection between them and the Watergate scandal.

© AP Photo, Charles TasnadiПрезидент Richard Nixon in the White house

© AP Photo, Charles TasnadiПрезидент Richard Nixon in the White house

Sometimes people use lies to draw attention to her figure. This might be attributed to the false statement of Donald trump, like his inauguration more people came than when Barack Obama first entered the presidential powers. People lie, to make amends for misconduct. So, during the summer Olympic games in 2016, the American swimmer Ryan lochte (Ryan Lochte) claimed to have been the victim of an armed robbery. In fact, he and the other members of the team, drunk, after the party faced with the protection when you spoil someone else’s property. And even among scientists, people seemingly devoted to the search for the truth, you can find counterfeiters: a pretentious study of the molecular semiconductors was nothing more than a hoax.

These liars gained popularity due to the fact that he lied blatantly and brazenly with the most devastating consequences. And yet this fraud is nothing supernatural. All these imposters, scams and selfish politics — just the tip of the iceberg of the lies enmeshed in all of human history.

It turns out that cheating is something skillfully manage almost everything. We can easily lie to strangers, colleagues, friends and loved ones, lie big and small things. Our ability to be dishonest is so deeply ingrained in us, and the need to trust others. Funny, that’s why we are so difficult to distinguish lies from truth. The mendacity is so closely connected with our nature that it is fair to say that a lie — human.

For the first time, the omnipresence of lies was systematically recorded by Bella Depaulo (Bella DePaulo), a social psychologist from the University of California at Santa Barbara. About twenty years ago Depaulo colleagues asked 147 people within a week to record every time, when and under what circumstances they tried to enter others into error. The study showed that the average person lies once or twice a day.

In most cases, the lie was harmless, it was necessary to hide the mistakes or to avoid hurting other people’s feelings. Someone used a lie as the excuse, for example, said that you didn’t take out the trash simply because did not know where. And yet, sometimes the deception was intended to create a false impression: someone claimed that he is the son of a diplomat. And although such misconduct and to blame especially not, later such studies Depaulo showed that each of us has at least once lied “seriously” — for example, hid the cheating or making a false statement about the actions of colleagues.

The fact that everyone should have a talent for deception should not surprise us. The researchers suggest that a lie as the model of behavior appeared after the language. The ability to manipulate others without the use of physical force is probably provided an advantage in the struggle for resources and partners, like the evolution of deceptive tactics, such as camouflage. “Compared with other ways of concentration of his power, to cheat easier. Much easier to lie to get someone’s money or status, than to hit on the head or Rob a Bank,” explains Sissela Bok (Sissela Bok), teacher of ethics at Harvard University, one of the most famous theorists in this field.

As soon as lie was recognized as a native human trait, sociologists and neuroscientists have begun to attempt to shed light on the nature and origins of such behavior. As and when we learn to lie? Where are the psychological and neurobiological basis of falsehood? Where for most is the line valid? Researchers say we tend to believe lies, even when it clearly contradicts obvious facts. These observations suggest that our tendency to deceive others, as well as the predisposition to become a victim of fraud, is particularly relevant in the age of social media. Our ability as a society to separate truth from falsehood is in great danger.

When I was in third grade, one of my classmates brought a sheet of stickers with racing cars, to boast. The stickers were just wonderful. I wanted to get that during the gym class stayed in the locker room and shifted the sheet from the backpack of a classmate. When the students returned, my heart was pounding. In a panic, fearing that I was exposed, I came up with a helpful lie. I told the teacher that two teenagers rolled up to school on a motorcycle, went to class, I rummaged through the bags and ran off with the stickers. As you might have guessed, this invention is crumbled at the first test, and I reluctantly returned it, stole it.

My naive lies — believe me, ever since I became more cunning, matched my level of trust in the sixth grade, when a friend told me that his family has a flying capsule that can take us anywhere in the world. In preparation for the flight in this aircraft, I asked my parents to pack me some lunch for the trip. Even when my older brother was choking from laughter, I still did not want to doubt the statements of my friend, and eventually his father had to say that I was divorced.

Lies, my lies, or lie my friend, was a common thing for kids our age. As the development of skills of speech, or walk, a lie is something one of the foundations of development. While parents are concerned about the lies of their children — for them it is a signal of the beginning of the loss of innocence — Kang Lee (Kang Lee), a psychologist from the University of Toronto, believes that this behavior in toddlers — signal: cognitive development on the right track.

To explore children’s lies, Lee and his colleagues used a simple experiment. They ask the child to guess the hidden from his toy in playable audio. For the first toys give an audio cue after the obvious barking dogs, meowing cats and children respond with ease. Subsequent playable sounds generally not associated with the toy. “You turn on Beethoven, and the toy ultimately machine,” explains Lee. Then the experimenter leaves the room under the pretext phone call is a lie in the name of science — and asks the kid not to peek. When he returned, he asked the answer and then asks the child a question: “You looked?”

As found by Lee and his team of researchers, most children can’t resist that look. The percentage of children that spying and then lying about it, depends on age. Among two-year offenders, only 30% are not recognized. Among three year old is lying every second. And to 8 years for 80% say that they did not.

Moreover, with age children start to lie better. Three and four year old children are usually just blurts out the correct answer, not realizing that this gives them a head. In 7-8 years, children learn to hide their lies, deliberately answering wrong or trying to make their response seemed a logical guess.

Five – and six-year-old remain somewhere in the middle. In one experiment, Lee used a toy Dinosaur Barney (character American animated television series “Barney and friends” — approx. Newochem). A five year old girl, who denied that peeked behind the screen, asked to feel a hidden toy before you answer. “And so she puts his hand under the fabric, closes his eyes and says, “Oh, I know, it’s Barney.” I ask: “Why?” She says, “It is purple to the touch””.

The lie becomes trickier as the child learns to put yourself in someone else’s place. Known to many as the model of thinking, this ability appears along with understanding other people’s beliefs, intentions and knowledge. Next support lies are the Executive functions of the brain, responsible for planning, attentiveness and self-control. Two-year-old liars from the experiment If showed the best results in tests of a model of the human psyche, and Executive functions, than those children who did not lie. Even among 16-year-old well lying teenagers were superior in these characteristics is unimportant cheaters. On the other hand, children with autism, as you know, having the delay in the development of a healthy model of the psyche, is not very good at lying.

The other morning I called Uber and went to visit Dan Ariely (Dan Ariely), a psychologist from Duke University and one of the world’s best experts in the field of lies. Although the interior of the machine looked neat, inside was a strong smell of dirty socks, and the driver, despite gentle handling, hardly focused on the road to your destination. When we finally got there, she smiled and asked me to give her a rating of five stars. “Certainly,” I replied. Later I gave a rating of three stars. I calmed myself with the thought that it is better not to mislead thousands of passengers Uber.

© RIA Novosti, Natalia Seliverstova | go to fotoreceptori taxi service Uber

© RIA Novosti, Natalia Seliverstova | go to fotoreceptori taxi service Uber

Arieli was first shown a keen interest in dishonesty about 15 years ago. Looking through a magazine during a long flight, he stumbled upon a test for intelligence. Answering the first question, he opened a page of answers to see if he was right. However, he glanced at the answer to the next question. Not surprisingly, continuing to solve in the same spirit, Ariel in the end we got a very good result. “After graduating, I realized that he had deceived himself. Apparently, I wanted to know how smart, but at the same time and to prove that I’m so smart”. This episode aroused Arieli interest in the study of lying and other forms of dishonesty, which it has retained to this day.

In experiments carried out by scientist with colleagues, volunteers give a test with twenty simple math problems. Within five minutes they have to solve as much as possible, and then they pay for the number of correct answers. Tell them to throw the sheet in the shredder before you say, how many tasks they solved. But in fact the leaves are not destroyed. In the end it turns out that many of the volunteers are lying. On average, they report six solved problems, when in fact the result of approximately four. In different cultures the results are the same. Most of us lie, but only a little.

The question that Ariel finds interesting, is not why so many of us lie, but rather why they do not lie a lot more. Even when the size of the reward is greatly increased, volunteers do not increase the degree of deception. “We give you the opportunity to steal a lot of money, and people cheat just a little. So something does not give us — the rest of us to lie to the very end,” says Ariely. According to him, the reason is that we want to be honest because in one way or another learned honesty as a value is presented to society. That is why most of us (if you’re not a sociopath) limit the number of times when you want to deceive someone. Just how far most of us are willing to go, Ariely and his colleagues showed it is determined by social norms, born of a tacit consensus, as, for example, take home a couple pencils from the office supply Cabinet at work has become tacitly acceptable.

Subordinates Kowenberg Patrick (Patrick Couwenberg) and its partners by jury in the superior Court of the County of Los Angeles would consider him an American hero. According to him, he was awarded the medal of the Purple heart for getting shot in Vietnam and participated in covert operations of the CIA. The judge also could boast an impressive education: bachelor’s degree in physics and a master’s degree in psychology. None of this was true. When he was exposed, he was justified by the fact that he suffers from a pathological tendency to lie. However, the layoffs did not save him: in 2001, the liar had to vacate judgment seat.

Among psychiatrists, there is no common opinion whether the relationship between mental health and craving for the hype, although people with certain disorders and indeed are particularly prone to certain types of fraud. Sociopaths are people with antisocial personality disorder — use of manipulative lies, and narcissists lie to improve their image.

But is there something unique in the brain of people, lying more than others? In 2005, the psychologist, Align Yan (Yaling Yang) and her colleagues compared the brain scans of adults of the three groups: 12 regularly lying about, 16 anti-social, but irregularly lying about people and 21 people without antisocial disorders and the habit of lying. Researchers have found liars at least 20% greater volume of pirovolakis in the prefrontal cortex, which may indicate that their brains have stronger neural connections. Perhaps it encourages them to lie, because they lie more easily than other people, or maybe it is, on the contrary, is the result of frequent fraud.

Psychologists, Nobuhito Abe (Nobuhito Abe) from Kyoto University and Joshua green (Joshua Greene) from Harvard scanned the brain of subjects with functional magnetic resonance imaging and found that dishonest people showed higher activity in the nucleus accumbens is the structure in the basal forebrain that plays a key role in the production of rewards. “The more excited your rewards from the opportunity to receive money — even in a completely fair contest — the more you tend to cheat,” explains green. In other words, greed may increase the predisposition to lie.

One lie can lead to the next, again and again, as can be seen from the calm and lies such serial scammers like Hoag. A neurologist from University College London Tali Sharot (Tali Sharot) and her colleagues in their experiment showed how the brain learns to stress or emotional discomfort accompanying our lies, so next time it becomes easier to cheat. On the brain scan of participants, a team of researchers focused on the amygdala gland — the land occupied in the processing of emotions.

The researchers found that every deception the reaction of the gland were all weaker, even if the lies become more serious. “Perhaps, small deceptions can lead to large,” says Sharot.

Much of the knowledge with which we orientirueshsya in the world, we are told by other people. Without our initial confidence in human communication we would be paralyzed as individuals and would not have had social relations. “We are very much received by the trust and the fact that sometimes we are fooled, the harm is relatively small,” says Tim Levine (Tim Levine), a psychologist from the University of Alabama at Birmingham who call this idea theory of truth by default.

Natural credulity initially makes us vulnerable to deception. “If you ever tell anyone that you are a pilot, it will not sit and think: “maybe he’s not a pilot?” Why did he say that he is a pilot? Nobody thinks,” says Frank Abignail Jr. (Frank Abagnale Jr), security consultant, whose crimes of youth, which includes forging checks and impersonating an airline pilot, served as the basis for the movie “Catch me if you can.” “Therefore, the fraud works: when the phone rings and the caller ID shows that it is the IRS, people automatically think it’s the IRS. They do not come to mind that someone could spoof the caller’s number”.

© Amblin Entertainment (2002)scene from the movie “Catch me if you can”

© Amblin Entertainment (2002)scene from the movie “Catch me if you can”

Robert Feldman (Robert Feldman), a psychologist from the University of Massachusetts, calls it “the advantage of the liar.” “People don’t expect a lie, do not seek it and often want to hear exactly what they say,” he explains. We almost do not resist the hype, which pleases us and soothes, whether it is flattery or a promise of unprecedented benefits from the investment. When we lie to the people who have wealth, power, high status, we are still easier to swallow this bait, as evidenced by reports of gullible journalists on allegedly robbed lochte, whose deception is quickly revealed.

Studies have shown that we are particularly vulnerable to the lie, which is consistent with our worldview. Memes that say, if Obama was not born in the United States, denied climate change, the blame for the September 11 attacks rests with the U.S. government and subject to other “alternative facts” as he called their statements about the inauguration of the adviser to trump, has become increasingly popular in the Internet and social networks because of this vulnerability. And a denial does not weaken their impact, as people evaluate the evidence in light of the existing views and prejudices, says George Lakoff (George Lakoff), Professor of cognitive linguistics at the University of California at Berkeley. “If you are faced with the fact that don’t fit into your worldview, you either don’t notice or ignore, or ridicule, or to be confused or harshly criticize him if you see him as a threat”.

A recent study, Brioni Suir-Thompson (Briony Swire-Thompson), doctor of cognitive psychology at the University of Western Australia, proves the inefficiency of factual information in the debunking of false beliefs. In 2015 Suir-Thompson and her colleagues gave about two thousand adult Americans one of the two statements: “Vaccinations cause autism” or “Donald trump said that vaccines cause autism” (despite the lack of appropriate scientific evidence, trump repeatedly argued that such a relationship).

It is not surprising that the participants who were supporters of the trump, almost without hesitation took note of this information when standing next to her was the President. After that, the participants got acquainted with the extensive study, which explains why the link between vaccinations and autism — delusion; then they were again asked to rate the degree of faith in this relationship. Now members, regardless of political affiliation, agreed that there is no link. But when re-checking a week later it turned out that their belief in the misinformation came down almost to the original level.

© AP Photo, Evan VucciСторонники Donald trump listen to his campaign speech

© AP Photo, Evan VucciСторонники Donald trump listen to his campaign speech

Other studies have shown that evidence to refute the lie, may even strengthen faith. “People tend to think that the familiar information is true. So every time you deny it, you risk to make it more familiar, making the denial, oddly enough, becomes even less effective in the long term,” says Soir-Thompson.

I myself have experienced this phenomenon for yourself soon after talking to Soir-Thompson. When a friend sent me a link to an article with a list of the ten most corrupt political parties of the world, I immediately posted it to the group in WhatsApp, where there were about a hundred of my school friends from India. My enthusiasm was caused by the fact that in fourth place in the list was the Indian national Congress, in recent years, involved in many corruption scandals. I glowed with joy, because I am not a fan of this party.

But soon after the publication of the links I found this list, which also included parties from Russia, Pakistan, China and Uganda, was not based on any numbers. It was a site called BBC Newspoint that sounds like a solid source. However, I found out that it has nothing to do with this BBC. In the group, I apologized and said that in this article, most likely written wrong.

This did not stop the other several times over the next day again to throw the link to the group. I realized that my denial had no effect. Many of my friends who shared a hostility to the Congress Party, were sure this list is correct, and each time, by sharing them, they unconsciously, and perhaps consciously, by making it more legitimate. To counter fiction with facts was impossible.

In this case, to prevent the rapid onset of unrighteousness in our life? No clear answer. Technology has opened up new opportunities for cheating, once again complicating the eternal struggle between the desire to lie and the desire to believe.