In January 2014 Daniel Granik in the Bundestag acted with quiet fury, the old soldier. High Assembly, he introduced himself like this: he arrived, they say, to Berlin not as a writer, not as a witness, and as a soldier. The soldiers who defended Leningrad (today St. Petersburg) from the Wehrmacht of Hitler. A very old soldier, born in 1919, but he had a clear head and he is able to stand for 40 minutes on his feet, if he was allowed to speak in the Bundestag.

After this speech Daniil Granin and Helmut Schmidt became friends, the one Schmidt, who was part of the 1st armored division participated in the advance on Leningrad. And with this speech the public I will remain in the memory of most Germans. Monday Granin died at the age of 98 years in his hometown of St. Petersburg.

“Death began silently and quietly to participate in the war”

In the Bundestag he spoke about the theme of his life, about the siege of Leningrad, about how Hitler wanted to conquer not only the city, not only destroy him, but forced to die slowly from starvation. “In December 1941 died of starvation 40 thousand people, and in February, were dying every day, three and a half thousand”. Granin looks at three of the bouquet of white flowers, followed by Angela Merkel (listens carefully), Joachim gauck (in terror), and in the hall a very different person, curious, but with a sense of shame, for the story of the siege of Leningrad much less known than the history of Auschwitz or Canterbury, one member yawns, apparently from exhaustion. Russian soldiers Granin speaks a clear language, but he is also a writer, and his speech is filled with terrible poetry: “Death began, silently and quietly, to participate in the war.”

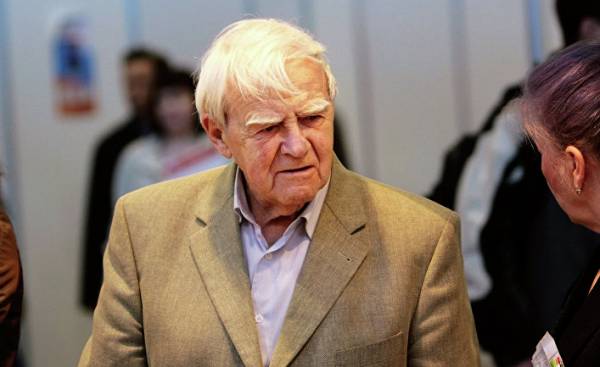

© REUTERS Tobias Schwarz Writer Daniil Granin reading in the Bundestag speech on the blockade of Leningrad

© REUTERS Tobias Schwarz Writer Daniil Granin reading in the Bundestag speech on the blockade of Leningrad

“One mother lost her three year old son,” according to Granik. Such fate he knows more than he would want for his documentary “Blockade book,” he spoke in the 1970-ies with many survivors. “The mother puts the corpse between the window frames, it is winter, and she cut off…” — here Granik breaks one of the employees of the Bundestag, she comes to the podium and invites him whispering in Russian, a chair —”… no, no, thank you”, said Mr. Granin, he prefers to stand, “she cuts the corpse every day for the piece to give my daughter something to eat. To at least to save your daughter.”

Granin said that while under a war-he understood the struggle of soldiers against soldiers, and that he could not forgive “the Germans”: “waiting for surrender, waiting for our death by starvation”. He does not say whether he forgave the Germans, and when.

In Russia, Granin long before his death received the status of immortal. He wrote four dozen books, novels, short stories, essays, took a bunch of posts in the unions of Soviet writers, accepted the award from the apparatchiks, later from Vladimir Putin and his people — and still remained a moral authority for the majority of Russian regardless of their political views. Granin could afford to oppose the official image of history. For example, he touched on the dubious role of the Communist leadership in the defense of Leningrad and documented as princely ate these frames, while at least a million people died of starvation.

Three years ago, Putin’s Minister of culture Vladimir Medinsky took on the thankless task to oppose this historical picture another, more Patriotic, in which party cadres led an ascetic life and heroically defended Leningrad. Medina had gone too far when he accused Granin in “lie”. And now, after his death, this Minister had to Express regret about the “end of the age” and his condolences in connection with death of the “honest worker of culture”, which “served the interests of the Fatherland and its people”.

How boring can one man take?

Granin knew better than many writers in Russia, how to survive and stay productive with the powerful hypocrites. For his critics it’s pronounced property of maneuvering is a problem and for him it was a necessary virtue. In his early books,such as “Going to storm,” he described himself as an engineer, everyday life and the achievements of Soviet engineers and scientists, created a literary, largely apolitical cult of reason, was thinking about the ethics of science.

When the bright critic of the political regime, Alexander Solzhenitsyn (“the GULAG Archipelago”) in 1969 was expelled from the writers ‘ Union as the public tried to abstain in the vote on the Board, but then under pressure still voted for the exclusion of Solzhenitsyn. A few years ago, he said about this in an interview: “My conscience is my business (…) I saw that I’d completely destroy themselves, but would not have helped Solzhenitsyn — and I joined the others and don’t regret it. There are situations when it is impossible to utter a word, I defined them for themselves and always stuck by this. After all, there are no saints”.

In his later books, he put it is the moral issues: “the Namesake”, 1975: How can the Soviet ideology combined with scientific honesty? “Painting”, 1980: How boring can one man take? The question of the conformity took his and Putin’s Russia. “During the war propaganda tried to convince us that the upper classes felt the same need as the population that the party and the people are one” — he said three years ago. “To be honest, and so it continues, the party is different now, but it’s the same kind of unity”.

Some books Granik translated into German, the latter an autobiographical novel “My Lieutenant” Helmut Schmidt wrote in the Preface: “the World is a priceless benefit. The book of Daniel Granin very convincingly reminds us of this”. Peace has remained for Granin a great theme. But he was one of those writers who in old age was not repeated and updated. He talked more about inner peace, love for his wife, who died in 2004. His last words in Parliament were: “the Most important thing is probably justice. And love. To life, to man.”