Hardened and fierce the presidents of Venezuela and of Turkey may live in different worlds, but their tenure takes on a striking resemblance.

Both see foreign conspiracies directed against them, and encourage its supporters, warning of the coup. Both run deeply divided countries and seem to benefit from such polarization. And both cling to power even when their countries are in crisis and significant economic disturbances.

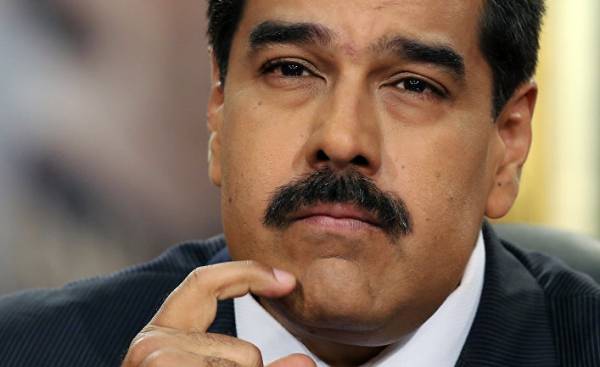

Of course, the grip of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro is weaker than that of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The government of Maduro weakened by weeks of mass protests that began after last month the country’s Supreme court terminated the powers of the National Assembly, controlled by the opposition. The decision was reversed a few days later, but only after it caused widespread outrage.

“That alone was enough to bring people to the streets,” said my colleague Amanda Erickson. “But many Venezuelans are already at the limit. Shortage of food led to the fact that most of the country is starving, and access to essential goods and medicines appears. Inflation is out of control, and crime became an everyday reality. Corruption and mismanagement led to the aimless spending of the huge oil reserves of the country”.

The worsening economic crisis has led to real and shocking consequences: three quarters of respondents a national study reported an average weight loss of 19 pounds (8.6 kg) in the period from 2015 to 2016, as a result of chronic food shortages. In the same period of time, the number of Venezuelans who are fed twice a day or less tripled, and now there are 10 million in a country with 30 million inhabitants. Increasingly, power outages, crumbling medical facilities, increasing the level of child mortality and infectious diseases.

The troubles of Venezuela, Maduro accused the intervention of the opposition, which controls the foreign (read: American) hand and gathered counter-protests and Pro-government militias known as “colectivos”.

The opposition demands to disarm these groups, to release political prisoners and hold new presidential elections — and they say that they will not cease to protest until these demands are met. The riots have led to 28 deaths this month, both sides blame each other for violence. The opposition, wrote my colleague Nick Miroff, perhaps hoping that their “ability to gather a huge crowd also sends a message to the armed forces of Venezuela” and raises the stakes for Maduro, whose power depends on the loyalty of the security services. The opposition publicly urged soldiers to defy the orders of Maduro on the suppression of protests.

“Every day, calling to the streets thousands of people, they try to show the armed forces how much can cost to support Maduro,” said the political scientist Margarita Lopez Maya to my colleagues. “And the government is experiencing a decline which seems irreversible.”

Maduro lacks the charisma of his predecessor, the late Hugo Chavez, whose populist revolution was tied to world oil prices and now have failed due to mismanagement and nepotism. But Maduro doesn’t listen to his critics, not to mention permission to hold new elections.

Why is there a comparison with Erdogan? First, the Turkish leader also doesn’t want to allow dissent.

After a failed coup attempt in July of last year, Erdogan and his government held a stunning purge of state institutions and civil society, arresting and removing tens of thousands of people — including many who likely were not (or almost) was not associated with the conspirators. On Wednesday, the Turkish authorities announced the arrest of another 1,000 people.

Indeed, Maduro has found inspiration in the actions of Erdogan. “You saw what happened in Turkey?” — said Maduro at a public event in August last year. “Erdogan will seem innocent compared to what will make the Bolivarian revolution when the right wing crossed the line and will be decided on a coup.”

Leaders also combines style bullies. Earlier this month, Erdogan had barely won a referendum that would abolish the parliamentary system in Turkey and will give him almost unlimited powers in his presidency. When the European election observers questioned the fairness of the vote, Erdogan attacked them, advising that they “know their place”.

During the preparations for the referendum, Erdogan was in various rhetorical battles with foreign governments, especially Western Europe and in Turkey, he constantly hinted at the threat posed to the interests of Turkey “crusaders” and “Nazi” Europeans. His favorite tactic is to rally the nationalist base against enemies, imaginary and real in other places. It is also a common technique in the populist regime that Chavez built, and now seeks to preserve Maduro.

“We tend to divide the Erdogan government and the Venezuelan revolution, but their approach to politics is much the same,” said Francisco Toro, editor of the news of the site “Caracas Chronicles”, in a recent (and interesting) podcast.

But despite their majority, the political reality for both the Maduro and Erdogan is a profound uncertainty. Increased international pressure, not to mention persistent dissidents in the streets, could deprive the President of most plans.

And while Erdogan is in a much stronger position, a referendum may yet prove to be a Pyrrhic victory. Weak advantage to his camp and breaking the rules — denies Erdogan’s overall mandate, which he had hoped. Soon he will be almost certain to blame for the growing problems of Turkey in the security and the economy, including the collapse of the tourism industry. Observers now also believe it possible that the long-divided Turkish opposition will again unite before the elections of 2019.

Erdogan and Maduro, who seem determined to remain in power, will have many sleepless nights.