One of the problems that continue to haunt the West that its policy of trying to drive Russia into a corner, lies in the fact that Moscow, though not with full resources of the Soviet Union, can still exert its influence in several regions of the world. Such myopia is repeatedly ignored Russia’s role in East Asia as an important factor for U.S. strategy in the region, although Moscow has established strategic partnership with China and conduct balanced economic policy towards Japan and Korea. The West underestimates the consequences of challenging games, which Russia is in the middle East in search of a balance between Turkey, Iran, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Israel, Egypt and Libya. Hackneyed story that “Russia is only a regional power”, and the persistent reminder of Russia’s GDP, equal to the gross domestic product of the average European or Asian countries, are underestimating the reality. Reality is that Moscow still has certain capabilities and resources to enable it to play the game on a global level.

Such bureaucratic tendency to look at Russia exclusively through European glasses superimposed stubborn refusal of Washington to maintain contacts with the Kremlin. On the background of the problems that cloud bilateral relations (Ukraine, Syria, election 2016, the problems of human rights, etc.), lack of effective communication channels for the exchange of information is a serious problem. As a direct result of the failure of communication is that its actions Russia may take the United States off guard, as she had done repeatedly in the middle East, including in Syria and Libya.

These two features of American policy towards Russia are of great importance, because the new fault lines that could generate disputes and conflict between Washington and Moscow, can go in unexpected direction. This may not be the intensification of fighting in Eastern Ukraine and not a random collision of NATO and Russian military aircraft over the Baltic sea. The reason for the confrontation could become a growing political crisis in Venezuela.

After the death of Hugo Chavez, his Bolivarian political movement barely holding onto power amid the weakening economy, which is literally dying because of clumsy government intervention and falling oil prices. Not have the charm and charisma of his predecessor, Nicolas Maduro, helplessly watching how the opposition is gaining strength and popularity, and today makes up the majority in the National Assembly. Advancing the well-trodden paths, Maduro is trying legal and illegal methods to get around the opposition and maintain his power in Venezuela. At the same time, he was desperately looking for ways to keep the economy from total collapse.

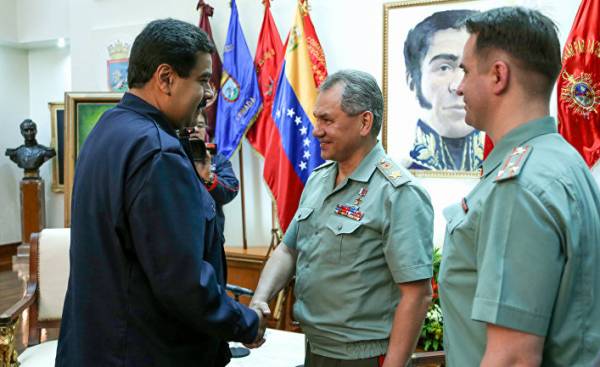

Chavez to get more space, turned to Russia as to an alternate source of investment in the energy and mining industry of the country, and as a supplier of military equipment for the army and security forces. In turn, access to Venezuelan oil and gas has become an integral part of the strategy of the Russian state oil company Rosneft, seeking to turn from the Eurasian energy supplier into an important player on a global scale. State energy company PDVSA, in search of cash and capital allowed Rosneft to purchase shares of its key and most valuable asset. For more financial injections from “Rosneft” it is even put up as collateral its shares in American oil refining and distribution company CITGO. For the Russian defense industry is also an important long-term contracts for the supply of military equipment and weapons of the Venezuelan army and the party militia, which is increasingly used for security.

In short, in recent years in Venezuela, as in Syria, Russia has emerged the need to support the current regime in order to preserve their investment. This need is increasingly growing, as the opposition made it clear that he considers illegitimate the capacity commercial presence in the country. Last year, the national Assembly has warned that it considers void the new contracts between PDVSA and Rosneft, and its members demonstrated their opposition by tearing up copies of the agreements between these companies. For Moscow sounded a loud and clear signal: if Maduro goes, with it will go and the Russian acquisitions.

As the example of Syria over the past six years, for this reason, Moscow strongly opposes regime change. Unrest continues in Venezuela, as Maduro seeks new ways to govern the country in a bypass Assembly through alternative institutions controlled by the followers of Chavez. In these circumstances, the disorder can turn into a full-scale uprising, and the regime in response, may attempt to suppress it by force.

Unlike Syria, Moscow will be very difficult to carry out intervention in the Western hemisphere. But Russia can still provide the government with Maduro is everything you need to maintain power, including to support him. This will certainly lead to the prolongation of the crisis.

But the problem of Venezuela is not on the agenda of Russian-American dialogue. Like, there’s no mechanism to ensure a “soft landing” that would allow a smooth hand over power to Maduro opposition. Moreover, Russia has currently no incentives to contribute to such an outcome.

The Washington consensus may be as many harp on the fact that the Russian aid in this matter is irrelevant, and that Moscow must pay for its decision to support the regime of Chavez-Maduro, deprived of their assets in the event of coming to power of the opposition. But Washington thought the same way about Syria, when it seemed to him that Bashar al-Assad is about to be overthrown. And look what’s happened. A long destabilization in Venezuela contrary to us interests. And now, Washington should think about how to encourage Russia to resolve the crisis.

Nikolas Gvosdev is a senior editor of The National Interest, a Professor specializing in national security issues and works at the College of the U.S. Navy.